Porosity of Parables

2024-2025

Charcoal powder, corn starch as binder

Silkscreen on cotton fabric

When I introduced myself and told them where I came from, here, people often responded, “Oh, you are from Jakarta? I heard the city is sinking.”

This is the parable how it came to be.

The colonizers built this capital on the ashes of the native’s coastal city that they had burned down and destroyed. The new city drew in, by fortune or force, people from across the world. As an attempt to make this region theirs, the colonizers built their new settlement in the likeness of their capital on the continent from where they came, formed with gridded straight canals. Even the meandering river was straightened. This time, it was even designed to be rectangular, similar to a military camp. They mainly used these canals as drainage, and also waterways, thus ships could enter the city to load and unload their goods. The apparent difference was that these canals were unbridged. Their very purpose was segregation instead of connection. Digging canals and removing the accumulation of sediment from the canal bed was a never-ending task. The strong-smelling vapor, nothing like the scent of rose, lingered. “Certainly this work is not suited for the dignified citizens of the city,” they said. The city committee forced the chained, enslaved people to work to their bones. Meanwhile, the dignitaries sat under the tamarind trees enjoying the breeze, sipping drinks served by the domestic enslaved women.

This fortified city was surrounded by tall walls made from large scales of coral stones taken from smaller islands within reach, to keep away those whom they considered as the most lowly humans, most prone to revolt. The colonizers had commanded the natives of the archipelago to complete the harsh task of digging up and hoisting the corals from the bottom of the sea. Many of them originated from the eastern islands. They were the defeated sides in kingdom wars or they were the last remaining survivors of massacres perpetrated by the colonizers. The divers' eyes were in constant pain due to having to keep their eyes open whilst collecting those corals under the salt water. Those colonizers knew that looking into another’s eyes should be based on equality, and that was not what they wanted. They would never want to look into the red, agonized eyes of those people. Out of sight, away from their skin. The colonizers mined corals excessively to continue building their city. As a result, those islands vanished. All these efforts were done to maintain their racial dominance, so they could own more and more.

Charcoal, corn starch as binder

Silkscreen on cotton fabric

Produced at Plaatsmaken

On display; coral stones ruins of the 17th Kasteel Batavia, North Jakarta. Then, the Dutch colonial settlement the city of Batavia was built on the ground of the destroyed Kingdom of Jayakarta. Under the command of J. P. Coen, coral building blocks were collected from the seabed of Kepulauan Seribu by the native population of Nusantara.

Presentation in The Living Prints, Plaatsmaken, Arnhem

Documentation by Koen Kievits

Presentation at Hotel Maria Kapel, Hoorn

Documentation by Bart Treuren.

“A conversation with Julian introduced me to the young-adult book, The Shipboys of Bontekoe (1924), a book by Johan Fabricius. The fictional book took inspiration from the journal of Bontekoe (1618-1625). Julian told me that the view of colonialism held by many Dutch is influenced by its portrayal in this book. Bontekoe is depicted as someone who is heroic, and a role model because of his perseverance when facing obstacles in life. In real life, Bontekoe helped Coen to find materials to build a colonizer’s settlement, Batavia. Bontekoe and his fleet stole hundreds of Chinese people from their lands and sent them to Batavia. Many of them did not survive on their way there. I read it from Arnoud’s article in Oud Hoorn magazine.

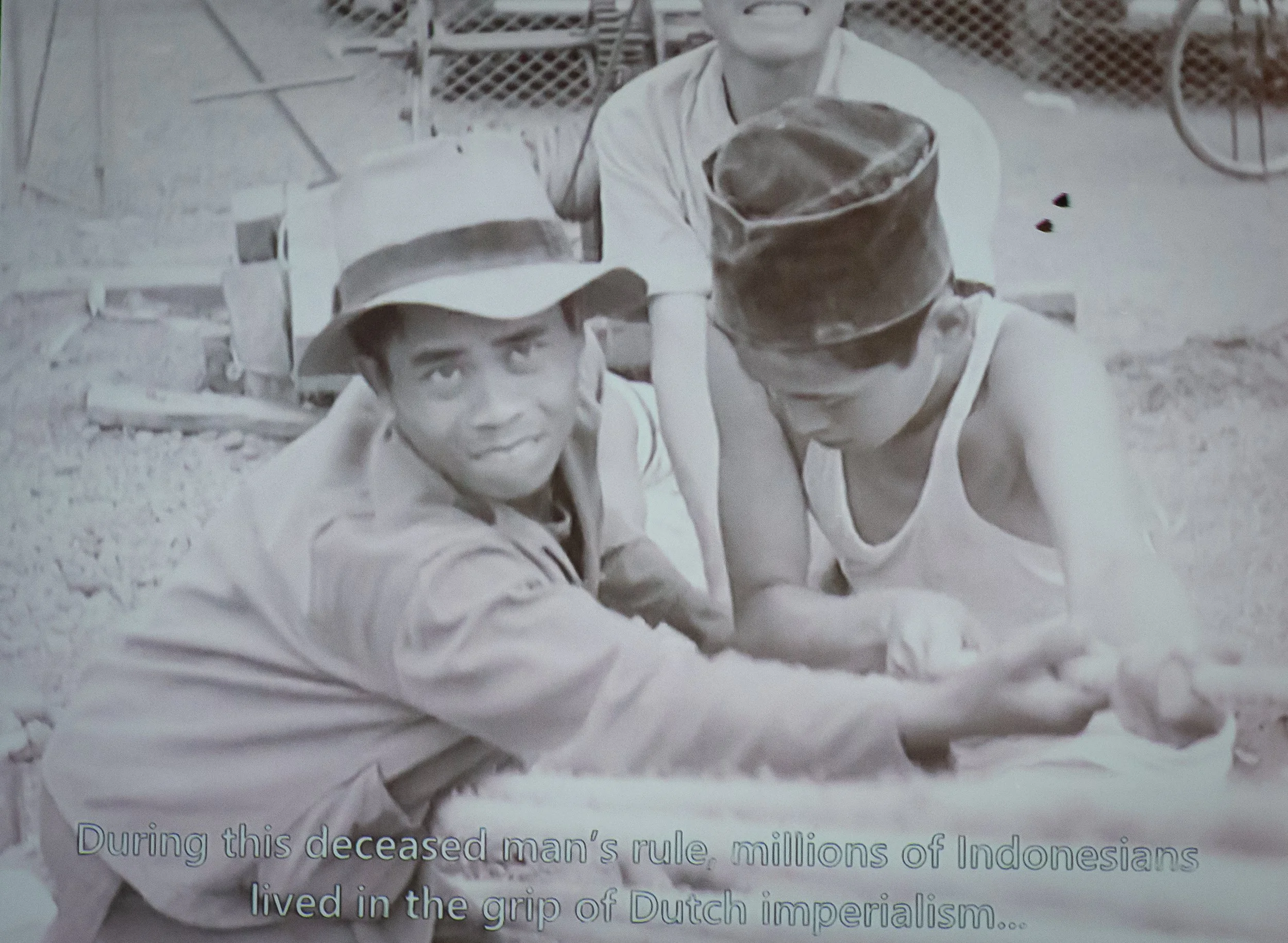

As we speak about the fictional shipboys, I remembered about the two boys from the urban kampung near the wall of Batavia. On the day I was taking photos in the area, they were passing by after swimming in the green-water canal beside it. They asked me if I could take pictures of them. When I sent them their photo, one boy expressed his gratitude for the photo. His friend is going to study at an Islamic boarding school. That means, they will be separated for a long time. I am glad that I can help preserve the memory of the friendship between them. That is a real-life friendship to me.”

-Excerpt from the script “Porosity of Parables”

Acknowledgments:

Hotel Maria Kapel

Patar Pribadi

Candrian Attahiyyat

Angga Cipta

Aziz Aminudin

Yuda

Marisella de Cuba

Julian Wijnstein

Arnoud Schaake

Stichting Plaatsmaken

Simon Groot Kormelink

Astrid Nobel

Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst

Stichting Stokroos